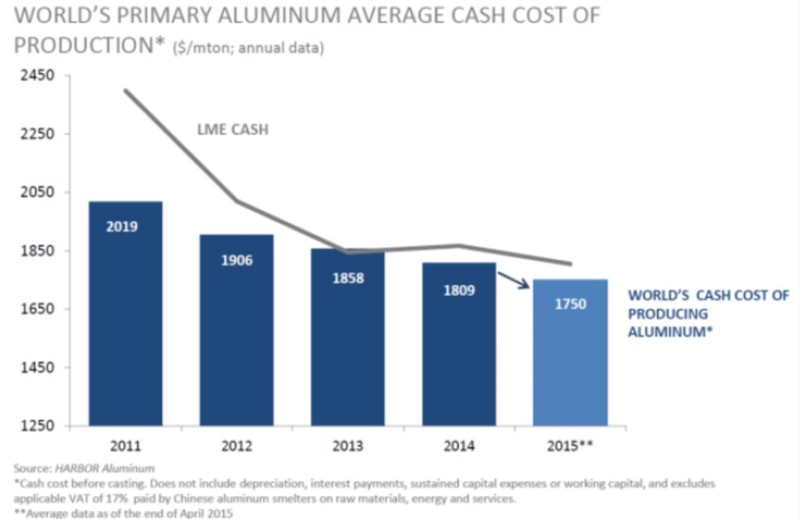

Production costs for smelters are highly dependent on the global economic environment, which affects oil prices, and the prices of other commodities, including those that create smelters’ input costs. For instance, during the global economic crisis in 2009, production costs for aluminium smelters decreased between 30 and 40% compared to the record high costs in 2008. Following the economy recovery in the years after, businesses’ production costs increased but remained lower than 2008 levels. Since 2012, smelters’ production costs have been gradually falling, reaching similar levels as in 2009 by end of 2015.

Another reason for decreasing production costs of smelters is the implementation of new and cheaper technologies with lower electricity consumption and higher efficiency, either in entirely new low cost capacities or through the replacement of high cost old technologies. This trend has been especially strong in China.

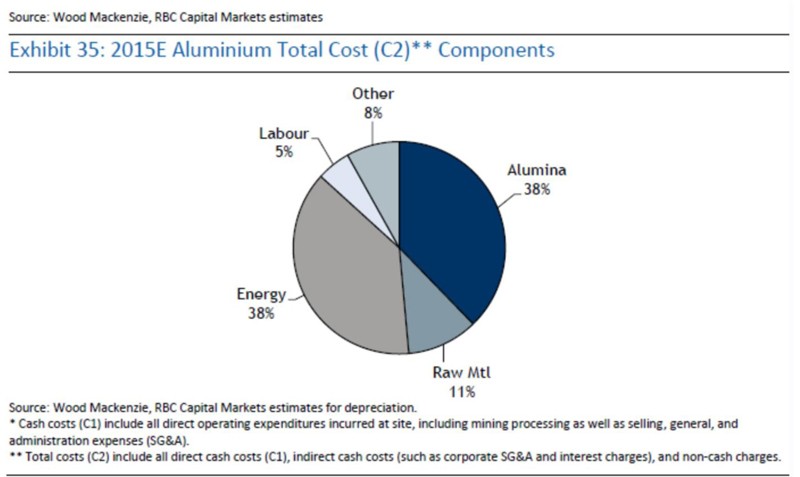

Alumina, electricity and carbon (anodes) costs represent the three major cost factors of every smelter. While alumina and carbon costs are mostly similar for smelters, electricity and labour costs significantly vary from region to region.

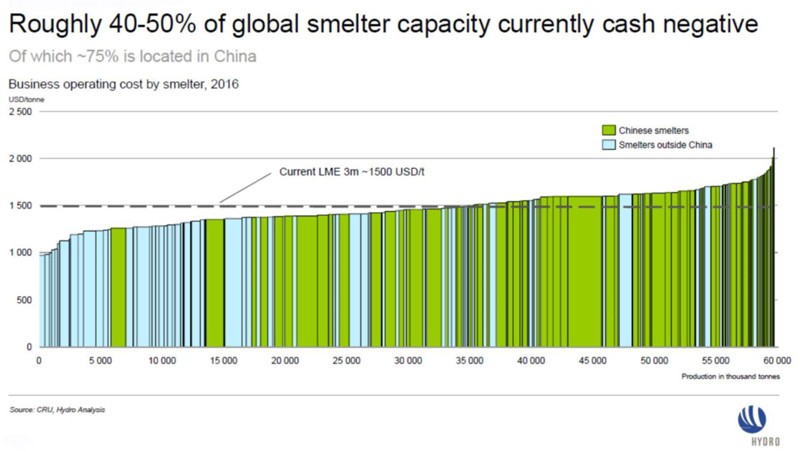

Four years ago in the spring of 2012, when LME cash aluminium price was just below US$ 1900 / tonne, some 60% of world’s (excluding China) primary aluminium producers had production costs above the market price. Today, with the price hovering around US$ 1500 / tonne again, up to 60 % of global production (ex China) would be unprofitable without premiums. With added aluminium premiums the percentage of loss making production is 45 – 50% of the global total (ex China) of around 28 million tonnes. Chinese smelters have approximately the same percentage of profitability, if looking at the SHFE aluminium price. How could this be possible?

The answer is that production costs for smelters around the world have decreased significantly in the meantime. Additionally, premiums sharply fell during 2015, after the record high levels reached during the previous two years, which has had an vital effect on smelters’ profitability.

The main reason for falling production costs has been a significantly lower oil price (falling from nearly US$ 100 /bbl in 2012 to below US$ 40 /bbl today), lower alumina prices (~ 35 %), lower electricity costs (for smelters whose electricity tariffs are linked to the LME aluminium price.)

However, the main cost reduction came from devaluation of local currencies (as was case with the Russian ruble and Chinese Yuan), along with the strengthening of US dollar against other major currencies in recent years.

Lower production costs can also be attributed to lower prices on the electricity market, while other smelters have built their own power plants or switched suppliers to get lower prices. In general, all input costs have decreased, including costs for wages and other benefits for workers due to currency devaluation and a lower number of employees at some smelters.

The lowest and highest production cost regions

Smelters with the lowest production costs are situated in the Persian Gulf, Canada, Russia, Iceland and South Africa, and are currently in the range US$ 1100 – 1450 per produced tonne. Smelter Ma’aden in Saudi Arabia, with a capacity 740 kT /y, is the lowest cost smelter in the world (~ US$ 1050-1100 / tonne), according to Alcoa, which holds a 25% stake. This statement is based on their own low cost alumina, electricity and anode production, and among other things, high relative production. The author believes that among the lowest cost smelters in the world are those situated in Canada, before all the Kitimat smelter (owned by Rio Tinto Alcan), due to its low electricity costs.

In contrast with 2012, new Chinese smelters have also joined the group of lower cost smelters, before all in the Northwestern province, Xinjiang, which has low electricity costs (due to low coal prices) and new low cost technology (consuming less than 13,000 KWh per produced tonne of aluminium). Smelters in China have been known as occupying the very top of the cost curve. If taking into account that the aluminium price is several hundred US dollars higher on the Chinese market (Shanghai stock exchange), compared to the LME price, these Chinese low cost smelters (of around US$ 1450 / tonne) have similar profits as the lowest cost smelters in the world (US$ 1100 – 1200 /tonne). Production costs of marginal smelters were also reduced during the last four years, from nearly US$ 3000 to around US$ 2250 / tonne. The highest cost smelters are also located in China, Australia and South Eastern Europe.

Electricity costs vary widely depending on the region, with power tariffs around US$ 20/ MWh in the Middle East, US$ 35-40/MWh in the USA and Europe, and around US$ 55/ MWh in China, after the latest additional subsides on electricity prices were introduced. The Chinese government has again lowered the on-grid coal-fired power tariff by RMB0.03/kWh (US$ 4.6 /MWh), starting from January 1, 2016. According to CRU, China’s primary aluminium production based on self-generated power accounted for 62% of total production in 2015. Chinese smelters with their own power plants benefit from weak coal prices in recent years. If coal prices remain weak and the electricity market is no longer constrained, large power end-users, including aluminium smelters, would be able to sign better deals for their power supply.

Smelters using the latest technology consume as little as 12.2-12.5 MWh/t of primary aluminium produced, whereas on average global smelters consume 14.5-15 MWh/t. Many smelters have variable power costs, when rates are a fixed percentage of the LME aluminium price.

The carbon anode manufacturers are mainly exposed to global oil and coal costs. Anodes are made from petroleum coke and recycled carbon mixed with liquid pitch. A significant amount of heat is used as the anodes are baked for 18 to 20 days at over 1,000 °C. As the oil and coal prices have tumbled in recent years, so has the cost base of anode makers.

The highest labour costs in the aluminium industry are in Australia, North America, Norway and in the European Union while the lowest are in China and India. But labour costs fall with higher productivity and between 2010 and 2016, Brook Hunt (Wood Mackenzie) predicted that labour costs would fall by 17% to US$ 89/t of aluminium produced.

New aluminium smelters will naturally be set up in regions where production costs are at the lower end of the spectrum. In the near term, Russia and the Middle East will most likely see new production capacities being built up, whereas in the long term Malaysia, Angola, Paraguay and Greenland could be further candidates.

Production costs of major producers decreasing

The declining aluminium price, lower oil prices and Russian ruble devaluation all helped UC Rusal to cut costs since its energy supply contracts are linked to the LME price. UC Rusal has long term contracts to supply power from low cost hydro power plants in Siberia. At the end of 2015 UC Rusal’s production costs fell below US$ 1500 / tonne. Rio Tinto Alcan has similar production costs, thanks to low cost smelters in Canada, powered also by low cost hydro power, with the Kitimat smelter having the lowest power tariff in the world (below US$ 6 /MWh), while its other Canadian smelters pay less than US$ 7 / MWh. Norwegian Norsk Hydro claims it lowered production costs to around US$ 1400 /tonne at the beginning of 2016, down from around US$ 1600 /tonne in 2014, while Alcoa’s costs have also probably gone down to around US$ 1600 /tonne by now, following an intensive cost cutting programme and capacity reduction (closure of high cost capacities). Chalco has the highest costs, around US$ 1800 /tonne, of all major producers.

Of the world’s 50 highest-cost smelters, 37 are located in China, and the average cost of production in 2015 was US$ 1,918 a tonne, 14 % above the average cost for the rest of the world, which is US$ 1,684 a tonne, according Wood Mackenzie.

The difference between major Western producers and China is that employment, not profit, is the main factor behind the decision of companies and local governments to continue operating smelters despite making losses. Based on the SHFE price in Q1, about 50% of China’s aluminium producers were unprofitable and should the price remain at current levels for an extended period, Chinese net capacity additions should start decreasing.

Higher production costs in the future are expected only in the case of higher oil prices (to be reflected upon other commodities in terms of main input costs), but also in extreme situations of higher political tensions and natural disasters, when supplies are being interrupted.