Demand for refractory products is evolving, forcing suppliers to upgrade their offers and processes to stay ahead of the game, while Chinese-origin raw materials are appreciating on the back of supply shortages, making productions costlier, Davide Ghilotti, IM Chief Reporter, finds.

The refractory industry has come to find itself between a rock and a hard place, faced with challenges on the supply side as well as in end markets.

While total demand for refractory products continues to reduce in the face of readjusting steel output, production is also moving downwards. For their part, suppliers cannot afford to stand still but must innovate, revisit their current models, relentlessly pursuing new markets and securing new business.

At the same time, a number of raw materials markets have become increasingly short in supply: magnesia, alumina, bauxite and graphite are only a few among several commodities affected, with drastic effects on prices.

This is triggering a rise in sourcing costs, denting refractory producers’ margins at a time of weak end-market consumption.

Monolithic refractories are having an overall better ride amid these tough times, compared with bricks and basic shaped refractories, but the challenges for the industry are there for all to see.

For its size and share of the global refractory industry, China remains a barometer of the health of the sector.

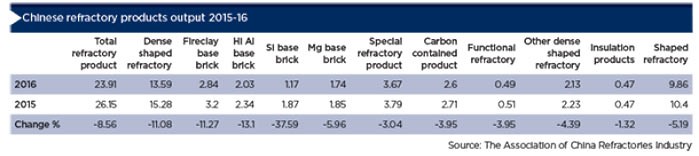

China’s total production of refractory products – this includes both shaped and unshaped materials, as well as insulation and other products – stood at 23.91m tonnes in 2016, according to data from The Association of China Refractories Industry.

This marks a drop of about 9% against the previous year, when output was a higher 26.15m tonnes.

All segments suffered a decline year-on-year.

Dense shaped refractories, which is by far the single largest category produced in China, lost over 1.2m tonnes (-11%) worth of output in 2016, falling below 14m tonnes. Fireclay base bricks and high-alumina bricks shared a similar fate, decreasing by 11% and 13% respectively, to 2.84m and 2.03m tonnes. Si-based bricks output dropped 38% y-o-y to 1.17m tonnes.

China’s refractories industry exhibited substantial growth in the last couple of decades, moving from just below 10m tonnes in 2000 to 32m tonnes in 2006, but today’s numbers are far from that peak.

It was not that much better on the export front: 2016 exports of Chinese refractory products (excluding source materials) were 5% down y-o-y.

The picture between segments is slightly mixed. While alkali refractory exports rose 5% to 867,600 tonnes, Al-Si based refractory exports fell 9%, to 662,400 tonnes. Shipments of other materials, at 110,700 tonnes, were down 32% y-o-y.

Back in March, IM reported that 2016 export value of both refractory products and source materials had reached its lowest level for the past five years at $2.57bn, down 12% on 2015 and 23% lower than 2014.

Demand for refractory products as a whole has been dwindling in recent years, mainly on the back of decreasing steel production. Steelmaking is the single largest end market for refractories, accounting for over 60% of end market demand.

Steel capacity in the western world has fallen, with facilities shut all over Europe and North America. At the same time China, which alone supplies over half of global output, has been forced to reduce output, and plans to gradually shut excessive capacity to bring the market back from oversupply.

This crucially meant that, while refractory demand in Europe fell due to local plants closing, Chinese demand also restructured, and was not in a position to pick up the slack created in the West.

India is arguably the sole destination where steel capacity is still increasing, and one of the few markets where new operations are being set up.

This has created fierce competition among refractory suppliers trying to elbow their way into the country. China has a prominent position on the Indian market, not only due to its logistical proximity. Some western suppliers are trying to ‘go local’ by teaming up with domestic companies or setting up operations in the country to try to bridge the geographical and cultural gap and gain real access to the market.

Monolithics on the up

Amid falling demand in main end markets, the buying patterns of refractory consumers are evolving.

With the widespread slowdown in steel output and weak pricing conditions, end users have seen profit margins shrinking. This has created an impending need for containing costs while maximising performances.

This shift is behind falling demand for basic refractory bricks, as more facilities move to monolithics.

While refractory usage globally remains dominated by bricks, a process of substitution is nevertheless taking place, with shaped products on the down and castables growing.

Currently, monolithics account for just over one-third (31%) of the total market in volume terms, with the remaining 69% share taken up by bricks, according to Calderys data released at the IM Bauxite & Alumina conference in Miami in March.

Even within bricks consumers, the vast majority (72%) of material consists of basic, magnesia and dolomite-based, brick products, while 28% is in acidic bricks. Conversely, the pattern of usage is essentially the opposite for monolithics, where 68% is in acidic mixes, and 32% in basic mixes.

According to Calderys, substitution between bricks and monolithics is «almost complete» in mature/developed countries – where castable usage is put at 40-50% of the total.

In developing countries, meanwhile, monolithics have not reached the same level of penetration, due to a number of factors that support bricks. These include low cost of labour, large availability of brick supply, and a lack of skills and expertise in monolithics. This underlines a long-term continuation of brick material usage in these markets, which will persist in the foreseeable future.

Raw materials: getting shorter

If demand from end consumers has dampened profitability as of late (due to a number of reasons which IM contributor, Richard Flook, explains in detail on pp 36-44), refractory producers have been struggling also with raw materials sourcing this year.

China, a leading producer of refractory minerals, has seen several of its key mineral production supply chains severely curtailed by environmental inspections by local authorities, amid an ongoing plan to curb the high level of air pollution in the country’s most industrialised areas.

This is actually a continuation of a policy that Beijing started in the first half of 2016. At that time, the clampdown on polluting industrial operations had mainly affected bauxite mining and brown fused alumina production (more on this later).

Since Q1 this year, environmental controls have intensified and spread to virtually all mineral production operations that are deemed polluting, as well as secondary processing and downstream sectors.

The immediate effect of the controls has been the shutdown of hundreds of operations in various provinces of China. In some cases the closures were temporary, while companies updated where possible their facilities to bring them in line with regulations. In many cases, however, small-size, obsolete operations were closed for good. Depending on the commodity, this took a sizeable share of production off the market.

At the time of publication, local sources told IM environmental teams are heading back to areas they had already inspected for a second round of checks. With elections in the ruling Communist Party due later this year, Beijing is keen to continue its clean-up action. It is early to assess the real impact this will have on future mineral production and supply, but several markets have been affected already, with lower output, falling inventories and rising prices.

Bauxite and alumina

Bauxite was among the first materials to be hit by the restrictions imposed by the Chinese government on pollution thresholds and operating processes of companies.

It first started in Q2 2016 with the intention to clamp down on illegal bauxite mining, which then added to Beijing’s strive to put a stronger effort towards environmental preservation. Facilities still relying on coal as an energy source were forced to switch to natural gas, or be closed. Shanxi and Guizhou were among the main areas affected. By the end of the year, many bauxite production operations had been shut for good.

Alumina, especially brown fused (BFA), suffered a similar fate. Stricter anti-pollution checks in main producing provinces of Shanxi and Henan hit production and started lifting spot prices already in August last year, as IM reported at the time.

Disruption to mining and production operations caused supply shortages and supported high prices for both bauxite and BFA well into the second half of this year. Securing volumes has become extremely problematic for some grades, such as high-purity bauxite 86%, 87% or 88%.

The bauxite shortage triggered a run for alternative materials. Andalusite suppliers told IM that demand from bauxite consumers has surged this year to date. Unfortunately, this material is also short. Andalusite production in both main origins – South Africa and Peru – was slashed in Q1 by heavy rain and flooding hitting mining areas. Many suggest 2017 supply will be insufficient to cover existing contracts, let alone meet demand from consumers who cannot find any bauxite.

Magnesia

The global magnesia market received a first shake in December, when China unexpectedly announced the scrapping of its existing duty regime and quota system for exports of magnesia products.

With hindsight, a first sign of the country’s intentions could be seen from late October. When the government announced the 2017 export quotas for all agricultural and industrial commodities, magnesia did not make the list.

Authorities went quiet for a few weeks until they finally announced that magnesia exports from 1 January would not be subject to duties nor quotas.

According to the preceding regime, export tariffs were set at 5% for caustic calcined magnesia (CCM) and 10% for both deadburned magnesia (DBM) and fused magnesia (FM).

The industry’s immediate reaction was one of widespread concern. Most market participants feared that a no-duty regime would lead to Chinese sellers flooding the international market with low-priced product, aiming to secure whatever demand was left after a long period of weakness in refractory end markets.

Confirming the industry’s fears to an extent, in the first few months of this year Chinese FOB prices for all magnesia products – CCM, DBM and FM – declined.

The downtrend was short-lived, however. As Chinese authorities tightened the controls over industrial pollution, many magnesia operations were affected and had to shut. Unable to produce, producers resorted to selling from stockpiles, which rapidly decreased. As short supply became evident, prices moved upwards again.

By early May, virtually all magnesia production facilities had stopped and fused magnesia had become unavailable in Liaoning province. Prices of all three products surged during the summer months, exceeding pre-quota scrapping levels.

It did not take long before the magnesia shortage came to affect refractories end markets. In June, the Refractory Industry Association of Yingkou, in Liaoning, recommended its member companies to raise sale prices of magnesium-based refractory products, to compensate for the rising raw material costs.

Graphite

As it did with magnesia, Beijing also scrapped duties on natural graphite exports, which were subject to a 20% tax until last year. New offers for flake and amorphous graphite decreased further as a result, despite several years of weakness due to oversupply and low demand. It seemed that another downtrend awaited.

However, the restrictions to mining eventually came to affect graphite production as well. Environmental inspection teams first reached Heilongjiang province, then Shandong. Operations closed, and those that remained in business have found it increasingly difficult to source quality ore.

Constraints to supply are starting to be felt, not least because the limitations on chemical processing have restricted acid-based graphite purification processes. Output of plus mesh graphite sizes has been particularly squeezed.

So prices, which had fallen in Q1, picked up again in Q2 and, by August, posted further upticks. Graphite remains in an overall better supply situation compared with bauxite or magnesia, but sellers see further disruptions to availability and aim to up their prices as a result.

All in, refractory suppliers are waging battle on various fronts. Contingencies on the raw materials side mean sourcing and production costs will remain higher for the foreseeable future, while evolution in end markets will affect demand for what products customers will want and how much of them they will buy. Refractory suppliers need to brace themselves as they see through a continuously-evolving scenario on both ends, in the hope that the industry will eventually settle and find a new normal.